Why Only the Best Employees Should Do the Hiring

It is very difficult for someone to chose a candidate that is better skilled than him or herself. Rather, he or she will likely chose someone that is just bit less skilled. People who are in reality are better skilled can easily be labeled as meaningfully less skilled or simply not suited to the vacant position.

When learning a skill, each of us starts with a low skill level. Our skill level then improves as time passes: by gaining experience, going to schools, having discussions with colleagues, training, and so on.

Some skills can be measured by hard facts, like the time it takes someone to complete a marathon or the number of repetitions in weight lifting. If hard facts are available, then we can rely on them. But more often than not, there are no hard facts and we have to rely on our own judgment.

Often what seems to be hard facts turns out to be unreliable when thinking about it. Consider the theoretical example of sending the best managers of the past decades to the final exams of an ivy league business school. I am convinced, most of them would only score low grades, because the exams are created to test the curriculum of the school and some traits like ability to memorize data and IQ, rather than the skill of being a good manager.

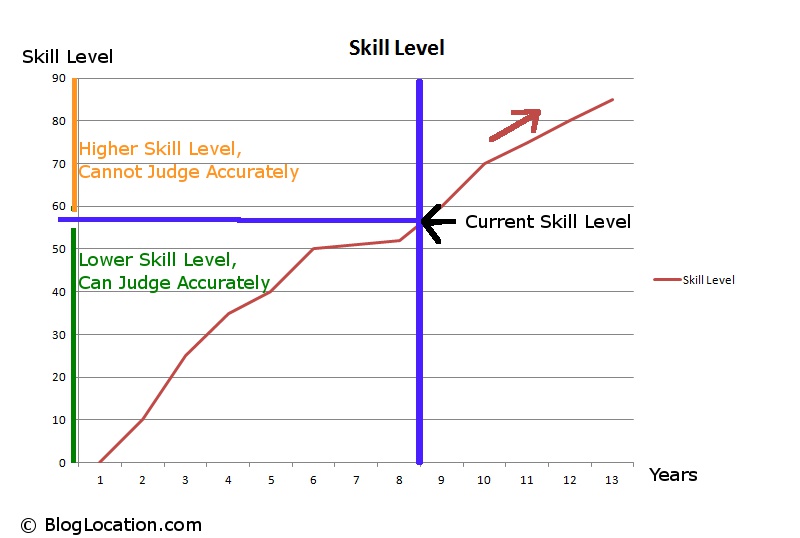

When not being able to rely solely on hard facts, we have to use our own judgment about the other person. We can asses the skill level of anyone with skills less than ourselves with some confidence. We can relate to them, because we have been there once in our lives or we can imagine being in his/her situation.

If someone has a higher skill level than ourselves, we have difficulty to identify that as such, because we ourselves have no experiences being at that higher skill level. This other person tells us things, which we cannot relate to. And all too easy, this gets labeled as less skilled than ourselves or as “not a good fit”, as it does not fit to what one is accustomed to.

To make the discussion more concrete and tangible, I will give some examples applicable to recruiting below, but first let’s illustrate it using a simpler example: the skill of writing. It will make the problem with assessing skill level understood.

We start school not knowing how to write. In school, we learn and our skill increases with each year until the end of High School.

Imagine a child comes to you and talks about his experiences with writing, his difficulties and his successes in writing. Very likely, you will know where the child is at in terms of skill level and be able to give him tips for improvement.

Imagine now that you are back in sixth grade. Another classmate comes and talks about his challenges and successes in writing and hands you a paper he has written. Are you able to judge, where he is in terms of writing skills compared to you: below, slightly below, the same, betters skilled?

You start by reviewing the paper he handed you. The teacher has not graded it yet, so you have to rely on your own skills. You read the paper and mark where the classmate has made a mistake. Then you count the mistakes and you will come to a conclusion.

This process, however, is seriously flawed. First, you probably don’t catch all the mistakes in the colleague’s paper. If you both make the same mistakes, you will not catch them. Second, you probably mark word as wrong that are in fact correct, but you yourself write wrongly. The more words you yourself write wrongly and the more convinced you are that you are correct, although you are not, the more mistakes you will mark in the colleague’s paper. This results in the following: the higher the skills of the colleague and the less of the same-as-your-mistakes he makes, the worse you will grade him. Simply because you don’t know any better.

But in school, you always knew quite accurately who was good in writing and who not. How was that? The answer is the teacher, who did the judging of skill level and whose judgment you probably accepted as authority on the matter.

To know the skill level of your classmates you either knew their grades or they talked to you about their experiences in writing. Their experiences were, of course, also strongly influenced by how the teacher graded their papers.

To sum up, there was an authority with a higher skill level who judged people on a lower skill level and solved the issue of ranking the students by skill level.

Let’s get back to recruiting. A person can accurately judge people below his skill level. He or she knows what it is like to be at that skill level and has been there at an earlier stage of his or her live. As soon as the skill level of the candidate approaches the level of the person doing the recruiting, the assessment gets messy. If the candidate is of higher skill level, then his more skillful behavior can be mistaken for a lower skill level.

In real recruiting, the skills are not as easily measurable by an authority as the above example with the teacher. That complicates the matter. Often skills are not hard facts, but involve soft factors, that are difficult to describe, measure, agree on, and come to conclusions on. Examples can be:

- Emotional Decision: Let’s assume for a specific business it is beneficial to give its customers a “90 days no questions asked full refund return policy”, because the additional business generated by it outweighs the cost of returns. A higher skilled candidate may know that from past experiences, but could have challenges in an interview with someone of lower skill level, who feels the loss and gets angry each time the company refunds to a fraudulent customer who never intended to keep the product.

- Amount of Distinctions: As people get older and more skillful, they start to make finer and finder distinctions in situations they work in. It’s no more black and white, but many shades of grey. For example, a highly skilled lawyer when asked about a case, may want to know a great amount of details before coming to a conclusion, because these details mattered in past cases. Without these details he might just answer: “I don’t know” or stay very vague. When asked in an interview by someone who is expecting a straight answer, the vague answer might be interpreted as he not knowing his field. For many questions, the answer “it depends” can show a high skill level. But a vague answer can also be viewed as less good answer than a straight answer from a candidate. The straight answer might be correct according to a textbook and work in most cases in practice. But someone whose able to identify the cases where another answer is more appropriate is probably still the better choice for the job.

- Wrong Interpretation of Candidate Limitations: A candidate who is highly learning driven and eager to improve his skills, will naturally focus on what he has to learn next. So he focuses on what he cannot do or does not know yet. Let’s assume he applies for a job he is qualified for. In the interview, when asked about his professional goals, he talks about what cannot do yet and therefore wants to learn. If the interviewer is not sufficiently high skilled in the topic compared to the candidate, then he will interpret this limitations as limitations of this candidate that other candidates do not have. It could be that all other candidates have these limitations, too, but are not even aware of it, because their skill level is so much lower, that they have not yet come in touch with these limitations. Only an interviewer with a high skill level himself can make such a call correctly.

An example could be a candidate for an entry position in a law firm admitting he’s lacking knowledge on specific past cases on some law. It would probably be interpreted as a negative point for that candidate compared to if he had not said it. Now consider it the following way: he is aware of the specific past cases, what might not be true for all other candidates. An interviewer who knows these past cases himself well (highly skilled), would spot that this candidate is far advanced, because he already has detail knowledge of the surrounding information of the law that these past cases apply to.

What can be done about it? The most highly skilled employees should do the recruiting. But who are the highly skilled employees? If the goal is high performance, then the best performing employees should do the recruiting. They are the most likely to choose candidates that will also perform highly.

Posted on

Last updated on